Wilson Sullivan got his big break working Barbara Seibel’s killing here in 1975.

As a crime scene investigator for Honolulu Police Department, he visited numerous crime scenes to collect evidence. He had to comb through multiple parking lots at Tantalus, searching for a clue that would lead to enough evidence to prosecute Paul Abraham Luiz for the murder of Seibel.

Incredibly, Sullivan was eventually able to match a tiny u-shaped plastic piece of a windshield wiper found by Seibel’s body to the car of Luiz, who was found guilty of murdering Seibel in 1976.

“It gave me a reputation among the detectives and the prosecutors that I put extra work into everything,” Sullivan said. “When I would meet different prosecutors and they would hear my name they’d say ‘Oh you worked on the Seibel case.’ It was a very well-known case.”

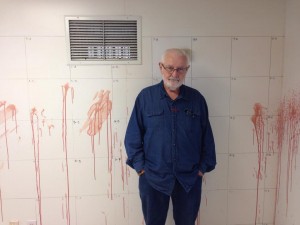

Sullivan’s expertise, decades of crime scene investigation experience, and remarkable work ethic have made him a valuable professor at Chaminade since 1996.

Sullivan was involved in crime scene investigation for the Honolulu Police Department for almost 30 years before suffering a stroke. He said he subsequently retired in 1994 after deciding it was unsafe for him to be driving vehicles.

During his 28 years of active law enforcement, Sullivan witnessed vast technological advancements, which significantly altered crime scene investigation.

Amongst these technological advancements were the introduction of computers, digital cameras, databases and DNA testing. Databases such as the Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS) and the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) were an “unbelievable step forward” for solving serial murders.

Sullivan said he wasn’t overwhelmed by the technological changes during the late ‘80s and ‘90s because he was young at the time.

“I lived for it and I ate it. I still do,” Sullivan said recently from his office in Chaminade. “This morning, for example, I was in here before 4 (a.m.) and I don’t start teaching until 9 (a.m.). It’s unbelievable how fast (forensics) changes. You’ve got to keep up.”

In 2002, after a brief stint at the Medical Examiners Office, he began teaching full-time at Chaminade in the Forensics Department. Dr. Lee Goff, who he used to work cases with, offered him the position of assistant professor.

Goff said he met Sullivan “over a dead body” and after a few homicides they established they were “more alike than many were comfortable with” and evidently a friendship developed. Their close-knit friendship and ability to “play well together” were one of the reasons Goff hired him.

“Sully had a broad knowledge of a number of fields, and I knew he would be able to interact well with students,” Goff said. “We needed that in the program at the time and it is still a necessity.”

Sullivan said it was just himself and Goff in the Forensics Department for at least 10 years. He wrote, as well as taught, many of the courses offered, such as: fingerprint analysis, photography, advanced photography, bloodstain analysis and crime scene investigations.

“We were both overworked, but when you like what you’re doing, what are you going to say?” Sullivan said. “I wouldn’t tell them, but if they had asked me to teach for free, I probably would’ve done it because I love it.”

In 2010, the Crime Scene Stimulation Facility (CSSF) was opened. Sullivan played an essential role in its design and implantation. The CSSF is used to re-enact crime scenes from past cases Sullivan has worked on.

He still has plans to improve the Forensics Department. One of his wishes is to purchase an old ambulance and convert it into a crime scene vehicle. He said this will help expose students to what it’s like to travel from crime scene to crime scene and set up equipment.

Sullivan said his two favorite courses to teach are bloodstain analysis and photography. He has been doing photography since the sixth grade considers it a hobby, as well as work tool, he said. Sullivan said he enjoys bloodstain analysis because it is a challenge, and to his knowledge he is the only person who officially teaches it in Hawaii.

“I can’t think of anything else I’d want to do,” Sullivan said. “How many people get up in the morning and want to go to work?”